Introduction

IRWANS.com & SEJARAHID In Islamic practice, the Qur’an and hadith (the sunnah of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ) are often used as sources of law. However, their status is not always the same. The Qur’an is regarded as the direct revelation from God, guaranteed to remain preserved until the end of time. Hadith, on the other hand, are records of the Prophet’s words and practices that were compiled after his death.

In reality, many rulings are not mentioned in the Qur’an but become “obligatory” because they are based on hadith. This creates a long-standing debate, especially when a ruling has no explicit basis in the Qur’an.

For example, in the case of circumcision: since there is no verse (nash) in the Qur’an, some Muslim scholars—particularly from the Hanafi and Maliki schools—do not regard circumcision as obligatory. Their stance is often misunderstood by those who accuse them of rejecting the sunnah, even though this is not the case. Such accusations usually come from people unaware of the diversity within the four schools of thought.

Some claim that refusing to use hadith where no Qur’anic text exists means rejecting the sunnah. However, there are two possibilities: first, the person might simply lack sufficient knowledge; second, they may indeed deny God’s guidance intentionally.

Case Examples: Stoning and Circumcision

A clear example is the punishment of stoning (rajm). The Qur’an does not prescribe stoning as a punishment for adultery. Yet, hadith narrations mention that the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ once applied it. As a result, some Muslims accept stoning as valid law, while others reject it because it lacks Qur’anic support.

Another case, closer to daily life, is circumcision. No Qur’anic verse explicitly commands it. However, because hadith record that the Prophet was circumcised and encouraged the practice, most Muslims consider it obligatory.

One hadith often cited in support of female circumcision is from Abu Dawud (a collection considered below the level of Bukhari and Muslim). The Prophet reportedly told a woman who circumcised girls: “Cut only a little, for that is more pleasing to the face and more honorable for the husband.”

The Four Schools on Circumcision

| School | Male Circumcision | Female Circumcision |

|---|---|---|

| Hanafi | Sunnah mu’akkadah (recommended, not obligatory) | Makruh (disliked, discouraged) |

| Maliki | Sunnah mu’akkadah (recommended, not obligatory) | Mubah (permissible, not obligatory) |

| Shafi’i | Obligatory (male and female) | Obligatory (highly debated in practice) |

| Hanbali | Obligatory (male) | Sunnah (recommended, not obligatory) |

These differences show that even within classical jurisprudence, scholars were not unanimous on circumcision. But in Indonesia, where the Shafi’i school dominates, circumcision is widely considered obligatory for both men and women. Those who question this ruling are often accused of rejecting the sunnah.

When Were Hadith Written Down?

It is important to note that hadith were only compiled long after the Prophet’s death. Prophet Muhammad ﷺ died in 632 CE, while authoritative hadith collections such as Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim only appeared in the 3rd century Hijri (about 200 years later).

This means hadith passed through a long process: oral transmission, selection, criticism of the chain of narration (sanad), and eventual codification. Unlike the Qur’an, hadith were not divinely guaranteed preservation. The Qur’an itself states:

“Indeed, it is We who sent down the Qur’an, and indeed, We will be its guardian.”

(Qur’an, Surah al-Hijr 15:9)

This verse is taken as proof that the Qur’an is divinely preserved. No similar claim is made regarding hadith.

The Position of Hadith in Relation to the Qur’an

Generally, hadith are understood to explain the Qur’an and provide details for verses that are general. However, from another perspective, hadith can also be seen as the Prophet’s interpretation of the Qur’an in his role as both political and religious leader.

After the Prophet’s death, authority logically shifted to the caliphs—Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, Ali, and their successors—who had the right to interpret the Qur’an according to their times. In this sense, caliphs and later scholars could issue new interpretations and rulings without being bound strictly to the Prophet’s hadith.

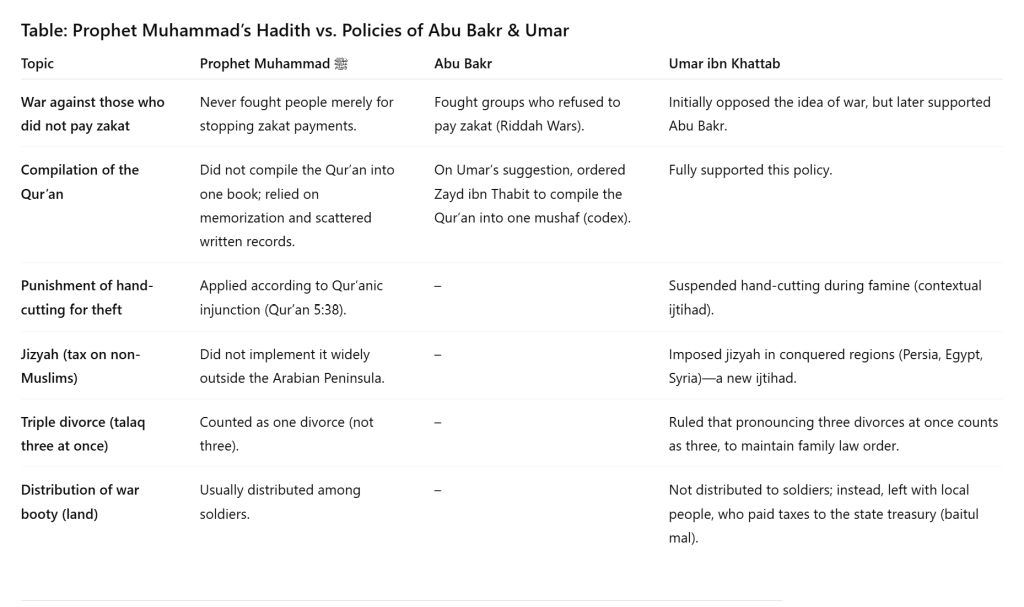

Examples from Abu Bakr and Umar

- Abu Bakr:

- Wars of Apostasy (Riddah): Prophet Muhammad ﷺ never fought those who merely stopped paying zakat, but Abu Bakr decided to wage war against them.

- Compilation of the Qur’an: The Prophet never ordered a written compilation, but Abu Bakr (at Umar’s suggestion) instructed Zayd ibn Thabit to collect the Qur’an into one mushaf.

- Umar ibn Khattab:

- Suspension of theft punishment: Although the Qur’an prescribes cutting the hand of a thief, Umar suspended it during famine.

- Expansion of jizyah (tax on non-Muslims): Umar applied it more broadly than the Prophet had.

- Triple divorce (talaq tiga): Umar ruled that three divorces declared at once would count as three, whereas under the Prophet it counted as one.

- War booty distribution: Umar changed the Prophet’s practice by not distributing conquered land but keeping it under state administration.

These examples show that early caliphs did not rigidly follow hadith but adapted rulings to new contexts.

Conclusion

The case of circumcision highlights an important reality:

- The Qur’an does not mention circumcision.

- Hadith does, but opinions vary among scholars.

- Two of the four schools (Hanafi and Maliki) do not regard it as obligatory.

This proves that hadith, while important, do not carry the same weight as the Qur’an, which alone is guaranteed divine preservation.

In Indonesia, the dominance of the Shafi’i school makes circumcision widely seen as obligatory. But history shows Islamic law has never been monolithic. Early caliphs and later scholars used their own judgment (ijtihad) to adapt laws.

Thus, the key question remains: if the Qur’an is guaranteed preservation while hadith is not, should the two be placed on equal footing as absolute sources of law? Or should hadith be seen more as historical interpretations—guidance for their time, but not binding forever?