Methodological Note

This essay employs a historical-sociological reading of early Islamic ritual development, distinguishing between:

(1) Quranic normative authority,

(2) prophetic-biographical actions situated in specific historical contexts, and

(3) later communal ritual formalization.

The analysis does not deny prophetic precedent, but questions how certain contextual actions came to be universalized in ways that may conflict with foundational monotheistic priorities.

Contemporary Narrative: Between Worship and Material Obsession

The phenomenon of millions of pilgrims shoving, crowding, and risking their physical safety merely to kiss the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad) is a repetitive sight every Hajj season. Numerous publicly available videos reveal a harrowing reality: men and women compressed together without separation, pushing and jostling in severely congested conditions simply to reach a single point of stone. When the pages of history are opened with a critical lens, a fundamental question emerges: is this act truly a universal theological mandate, or is it better understood as an inherited symbolic practice rooted in prophetic biography rather than Quranic obligation? A close reading of the Quran suggests that this practice is closer to historical-emotional inheritance than to mandatory ritual prescription.

Tragedy at the Corner of the Kaaba: When Life Is Lost to a Material Object

In the midst of dense crowds, heartbreaking scenes frequently occur. Video clips show pilgrims, particularly women, being crushed and struggling with all their might among seas of bodies merely to touch the stone—a visible indicator of spiritual disorientation. These stampedes illustrate how fixation upon a material object can eclipse humanity and common sense. Many pilgrims are ultimately swept away by the mass current, failing to reach the stone and departing not with serenity, but with injury, trauma, and lasting physical and psychological scars.

Ignorance and the Paralyzed Role of Global Islamic Scholars

It is deeply regrettable that this “black stone scramble” has persisted for decades, sustained by widespread misunderstanding. Many pilgrims believe that kissing the Hajar al-Aswad represents the pinnacle of Hajj perfection, whereas in Islamic jurisprudence it is categorized as Sunnah (recommended), while preservation of human life and prevention of harm are Wajib (obligatory). This contrast exposes a troubling absence of decisive leadership from religious authorities. Rarely do scholars explicitly discourage or restrain this practice under dangerous conditions, despite well-established legal principles prioritizing harm prevention over optional acts. This educational vacuum allows inherited myth to overpower the logic of Tauhid, leaving pilgrims trapped within collective emotional momentum rather than guided by theological proportion. One may reasonably ask whether contemporary scholars adequately interrogate the historical context behind why the Prophet Muhammad kissed the stone in the first place.

The Absence of Quranic Basis: Purifying Monotheism from Material Mediators

The first reality to acknowledge is that not a single verse in the Quran commands Muslims to kiss, touch, or venerate the Hajar al-Aswad. The Quran consistently directs devotion toward Allah alone, a transcendent reality not confined by space, form, or physical object. Within a framework of strict monotheism, the absence of explicit instruction should function as a clear boundary. Quranic silence regarding this practice strongly indicates that its authority rests upon inherited tradition rather than primary revelation.

From Shepherd to Famous People: The Roots of Historical Memory Surrounding Muhammad

History records that the significance of this stone in Muhammad’s life began long before his prophethood, during the reconstruction of the Kaaba by the Quraysh. A fierce dispute arose among tribal leaders over who would possess the honor of placing the Hajar al-Aswad in its position. Bloodshed was narrowly avoided through a compromise: the first person to enter the sacred area the following morning would arbitrate. Muhammad, then approximately thirty-five years old and already married to Khadijah, was the first to arrive. With diplomatic ingenuity, Muhammad spread his cloak, placed the stone at its center, and asked each clan leader to hold an edge of the cloth and lift together. This solution impressed the tribes, who conferred upon him the title Muhammad al-Amin (Muhammad the Trustworthy). This episode elevated Muhammad’s social and political standing in Mecca and its surroundings, making him a figure of national relevance even before his prophetic mission. It marked a transformative moment: from an obscure orphan and former shepherd to a recognized and respected famous public figure.

The Conquest of Mecca: An Emotional Reunion with a Symbol of Victory (From Zero to Hero)

When the Conquest of Mecca (Fathu Meccah) occurred in 630 CE, Muhammad—who had been driven out of Mecca in 622 CE—returned as a victor with approximately 10,000 Muslim troops. Muhammad entered the Kaaba and, upon seeing the Hajar al-Aswad, kissed it. While no early source records his inner motivation, a plausible sociological interpretation is that the stone carried personal-historical resonance connected to a formative episode in his earlier life, namely the dispute over Hajar Aswad’s placement that first established his public reputation as al-Amin (the Trustworthy). This reading does not claim certainty; it offers an alternative lens through which to view how a biographical memory may later have been ritualized by subsequent generations. The difficulty arises when a contextual personal act is transformed into a universal standard of worship as if it possessed inherent theological value.

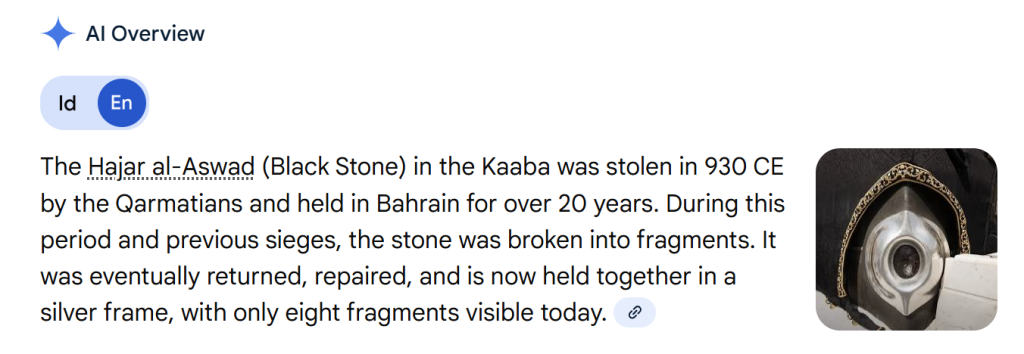

Meteorite Reality: Physical Vulnerability versus Claims of Sanctity (Not a Heavenly Stone)

History records that the Hajar al-Aswad was stolen in 317 AH (930 CE) by the Qarmatian movement led by Abu Tahir al-Jannabi, who massacred thousands of pilgrims and transported the stone to Bahrain for twenty-two years. After a ransom was paid, the stone was returned in broken fragments, later encased in silver. Materially, this demonstrates the characteristics of a physical object susceptible to damage, fracture, and wear. This does not negate its historical importance, but it does underscore its non-divine nature. Venerating a physically vulnerable stone as if it possessed inherent sacred power confuses historical symbolism with metaphysical sanctity.

Umar ibn al-Khattab’s Critique: The Companion’s Logical Tension

Doubt regarding the rationality of kissing an inanimate object is recorded in the statement of Umar ibn al-Khattab: “I know that you are only a stone that can neither benefit nor harm. Had I not seen the Messenger of Allah kissing you, I would not have kissed you.” Umar openly affirms that the stone itself possesses no agency. His action is grounded solely in imitation of prophetic precedent, not belief in intrinsic power. This remark reveals early awareness of tension between rational monotheism and inherited ritual imitation.

The Risk of a Functional Idol: Preserving the Purity of Tauhid

Transforming a contextual prophetic action into a universally pursued Sunnah—even at the cost of human life—constitutes a dangerous shift in perspective. If the Hajar al-Aswad carried personal-historical meaning for Muhammad, then for the wider Ummah it remains a physical object without divine authority. Treating the stone as a source of blessing or spiritual energy effectively assigns it functional religious agency. Even when doctrinally denied, such practice risks turning the stone into a functional idol. It becomes a material mediator between believer and God, contradicting the essence of pure monotheism.

Conclusion

Kissing the Hajar al-Aswad has no Quranic basis as a universal mandate of worship. The practice is more accurately understood as an inherited historical expression that was later institutionalized without sufficient contextual awareness. The Hajar al-Aswad should be regarded as a valuable historical artifact, but as an object possessing no power whatsoever. For anyone other than Muhammad, the stone is merely physical matter. When positioned as a mediator for blessing or divine proximity, its function converges with that of an idol. In this sense, uncritical veneration risks transforming the Black Stone into a Stone Idol.